Over the last year, the WithIn Collaborative has been working alongside parents and leaders from tribal lands in and around Humboldt County – and with medical practitioners from Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Eureka, CA. Our focus: How to better the birth experience of Native parents at Providence St. Joseph Hospital. We quickly became known as the “Better Birthing” team.

Our team, made up of practitioners and parents from the hospital and Native organizations, heard from Native families that they often experienced disconnection and fear alongside the joyous overwhelm of birth. We heard stories of Native parents struggling to support their birthing traditions in a hospital environment. And we heard too many stories that featured cultural ignorance and missed opportunities for comfort and care. We came to understand, through these stories, that the experience of many Native parents giving birth at a hospital is intimately connected to the devastating history of how the state and institutions treated Indigenous people in the last two centuries.

As our team retold these stories to one another, and endeavored to understand the barriers and opportunities for healing, we came to believe that the institutional birth experience holds the possibility for repair and connection. What emerged from our sensemaking are multiple efforts that seek to provide the care Native parents want versus what they have experienced in the past. These include:

- Changing California state law.

- Leveraging a parents’ birth plan to co-create a culturally responsive birth environment.

- Changing the hospital environment to reflect the communities it serves.

Changing California state law.

Until recently, California state policy required that all families register the birth of a child with the hospital by the tenth day of life. This practice often conflicts with the period of sacred ceremonial blessing and naming of a newborn in Native communities. On June 22, 2022 California Governor Gavin Newsom signed CA State Bill AB 2176 into law. This bill simply extends the time all families have to register the birth of their child from 10 to 21 days.

The effort to change state policy emerged from the stories told to the Better Birthing team by Native parents and hospital administrators. We heard from parents how offended they were by the constant requests by hospital staff to reveal their newborn’s name before they left the hospital. In turn, hospital staff were frustrated that their attempts to prevent families from incurring the additional cost and paperwork involved if parents missed the 10 day deadline to register their child was experienced as ignorance and cultural insensitivity. This new law removes that irritant in the relationship between Native patients and medical staff. More importantly, it signals the willingness of the state to be more respectful of sovereign First Nations practices.

Leveraging a parents’ birth plan to co-create a culturally responsive birth environment.

Often when Native parents arrive at St. Joseph hospital to give birth, it is their first experience of the hospital. Many Native families live far from the hospital; sometimes driving over two hours to give birth. Parents we spoke with felt unwelcome, nervous about how they would be received, and unclear what choices they had in birthing experience at the hospital. One mother told us that she opted not to bring a traditional baby basket because she did not know if the practice of putting her baby in the basket after birth would be welcome. Another parent concluded the hospital was racist after she was given a drug test at intake that is administered to all parents.

To promote better communication and cooperation between parents and the hospital, the Better Birthing team is experimenting with a birth plan. Birth plans are not a new idea. They typically express a parents’ hope for the birth experience and make requests of the medical team. Those hopes and requests are often out of sync with the hospital’s requirements or the medical realities of that parent’s birth experience. This birth plan attempts to bridge the gap in cultural responsiveness and knowledge between parents and the medical team.

The medical staff present at a birth are often unaware of how a patients’ race, ethnicity or religion impacts their decision making and preferences. The birth plan prompts parents to clearly consider and describe how their traditions influence their decision making around the birth experience. For example, if it is the Native parents’ tradition to keep the placenta or umbilical cord, the birth plan prepares parents to bring a cooler for storage; sign a specific form of release; and designate a family member for transport. The birth plan is also an opportunity for the hospital to express its support of Native traditions by stating, for example, that Native baby baskets and traditional medicinal plants are welcome in the birthing rooms.

Likewise, parents are often unaware what hospital procedures are elective versus required. The birth plan we are testing makes explicit what is standard medical practice at St. Joseph Hospital. It provides very clear decision points so parents can know ahead of time what their preference is, for example, to have intermittent or constant baby monitoring, or whether they want an intravenous lock for medical interventions if it’s not clearly warranted.

The birth plan is still being tested. We’re currently exploring how to best integrate the birth plan into the parents’ arrival at the hospital; a moment that can be chaotic and emotional. One clinic is experimenting with reviewing the birth plan with parents at their 26 week appointment. The hope is that the birth plan at least initiates conversation that leads to greater cultural responsiveness from care providers and more holistic care for the birthing parent.

Changing the hospital environment to reflect the communities it serves.

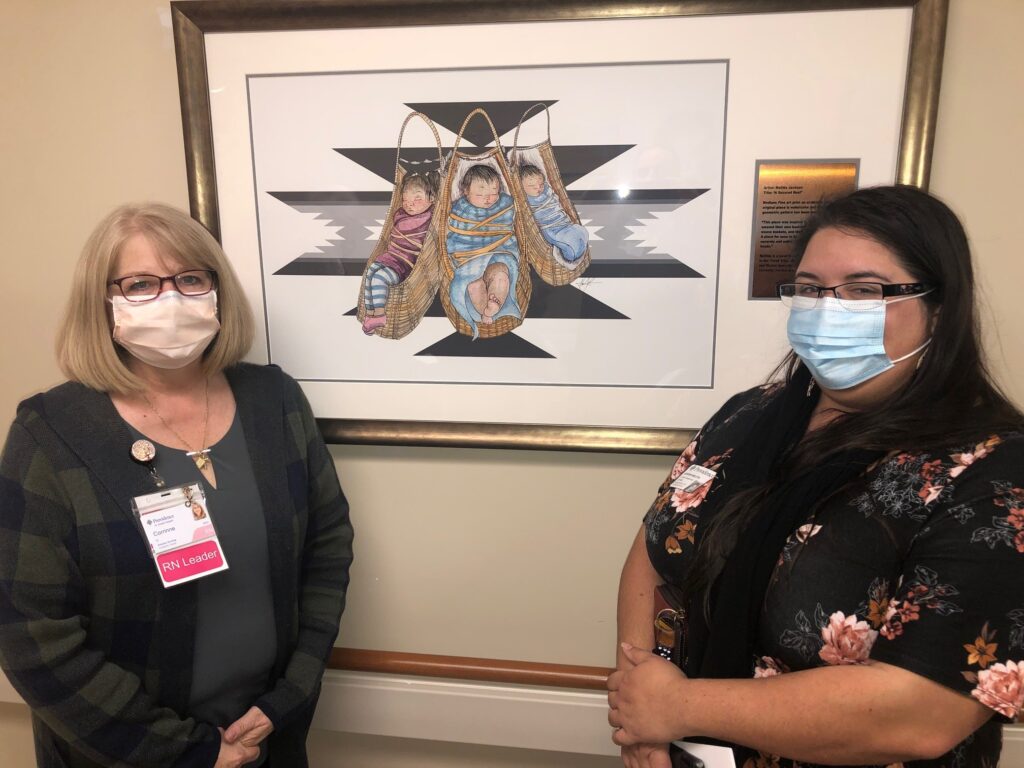

As luck would have it, the hospital had recently received funding to redecorate its birthing unit when the Better Birthing team began its work together. This allowed the hospital administration to address early feedback we received from parents about what it felt like to be at the hospital as a Native person. Parents observed that the pictures hanging on the walls did not look like those giving birth there, and that the birthing unit felt sterile and institutional.

The Better Birthing team and additional Native leaders worked with the hospital on creating a space that was more representative of the community in multiple ways. They suggested that the hospital bring elements of the incredible rivers and trees of Humboldt County into the space for both inspiration and because it “felt like home”. The team selected pictures for the walls that were not only racially representative but show women breastfeeding and men nurturing their newborns. Finally, the hospital was able to purchase incredible artwork from local artists that reflect native traditions.

And there is more to come.

Multiple threads of the work continue as does the work of building more trusting relationships between the hospital and the communities it serves. We recently learned that the work of the Better Birthing team has received the 2022 Leighton Memorial Award by the CARESTAR Foundation. This award is given to a collaboration in a rural or tribal area that has demonstrated success in addressing inequity in hospital care. We are told that the selection committee decision was unanimous. Beyond the immense honor of receiving the award, it also funds our continued work together. We are now engaged in considering the possibilities of what comes next.